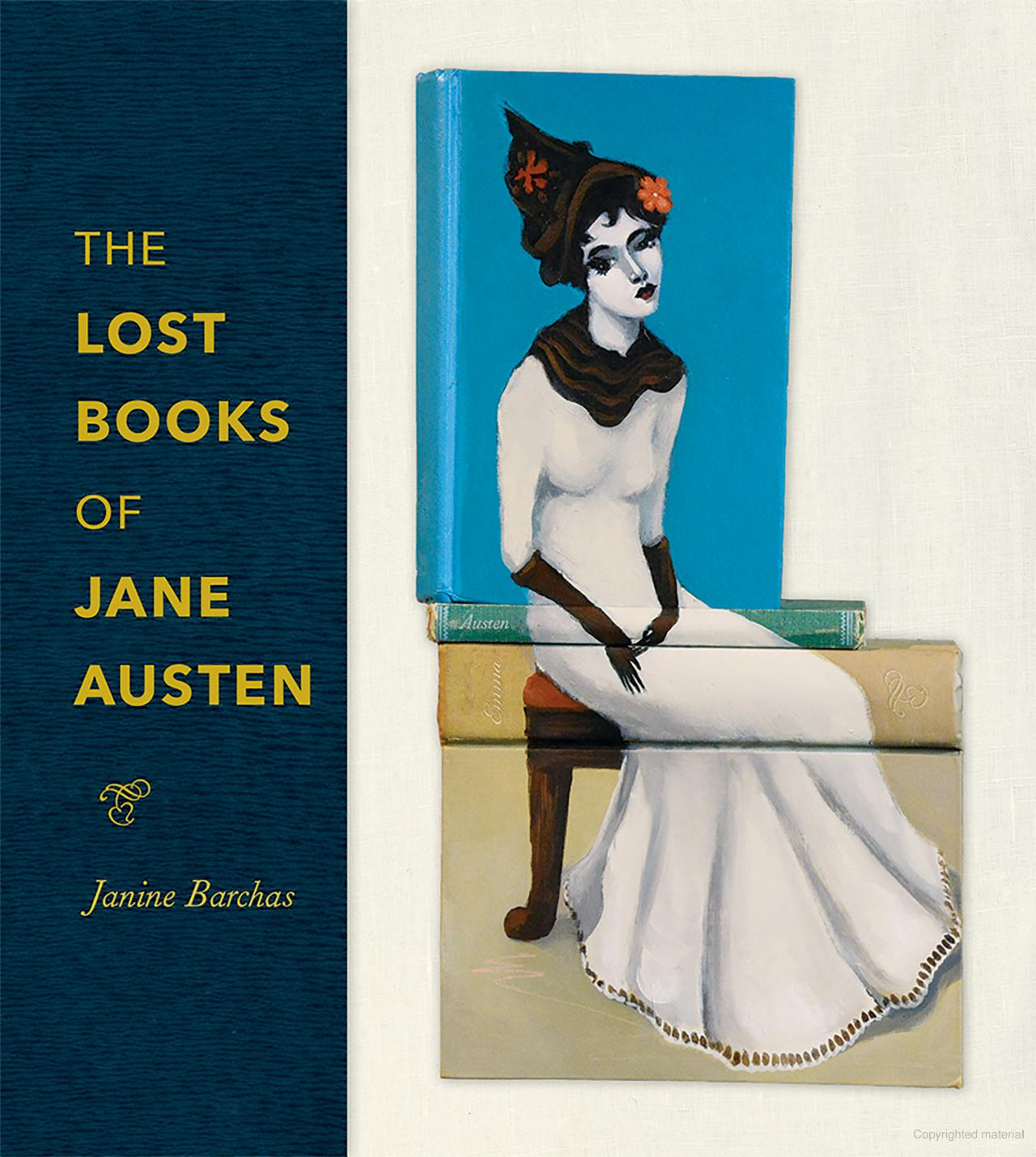

The Lost Books of Jane Austen

The Lost Books of Jane Austen is the title of a book by an American, Janine Barchas. How exciting it sounds! What are these lost books of Jane Austen, and is she about to unveil some undiscovered, unpublished manuscripts to the world?

A couple of years ago a book that is possibly an unknown early work by Austen was reprinted: Two Girls of Eighteen, edited by P.J. Allen.

Sadly, there are no such revelations in Barchas's book. The title merely refers to the many different editions of Austen's novels which have appeared over the two centuries since she wrote them, and which Barchas apparently collects.

This is an amusing hobby if you have got the space, and Barchas reproduces countless cover designs and title pages in different styles, typefaces and formats, with or without illustrations, according to shifting tastes, and the sort of readership the edition was aimed at. Some are meant to impress, others to lure the reader with promises of excitement or gooey romance. But is there any serious point to this? The book, which is published by a University Press as an academic study, is not in my view scholarship, because it does not ask any worthwhile questions or answer them. It does not discover anything new. Barchas starts by telling us that 11-year-olds can be misled by an inappropriate book cover into expecting Mr Darcy to be a vampire, and then goes on to argue that we need to study hundreds more silly and misleading book covers.

Yes, really.

The blurb tells us "Janine Barchas demonstrates that literary works are canonized not by first editions, but by cheap reprints." What a peculiar assertion. At one stroke she has succeeded in insulting Jane Austen and all her loyal enthusiasts.

If cheap editions ensured canonical status then wouldn't all the cheapest penny-dreadfuls of the 19th-century have ended up on the lists of "English Literature" once that subject became established as a matter for literary study? In fact the choice was influenced by many things, but cheapness was never one of them. Since the 1830s, publishers such as Bentley had been issuing reprints of older novels that had acquired some reputation among the general reading public - a public that was overwhelmingly middle-class. And many publishers issued in series books that were acknowledged as "classics" - J. M. Dent's Everyman books being one of the most celebrated. There were also the Thomas Nelson Classics in their dark blue covers. The inclusion of Austen was based on popularity yes, but also reputation among cultured people.

What maintained that reputation and turned it into lasting esteem? One important factor in a book attaining classic status is that it can be read on many levels. The earliest readers of Jane Austen enjoyed her primarily as comedy - this is evident from contemporary reviews. And it explains why Mrs. Gaskell recommended Charlotte Brontë to read Emma, as Austen's best book. (Poor Charlotte Brontë, who had as much sense of humour as she had ability to play the trombone, was not amused.)

A large contingent today frankly enjoy Austen as chick-lit, stories about young women who are in search of romance and husbands. That these readers are numerous was demonstrated by the reception of the TV series Sanditon. The books reassure girls that there are some decent men around, men with principles who are looking for wives even if they don't yet realize it. Other readers enjoy her for presenting the manners and customs of a more polite age, while some enjoy her for her dignified, Georgian, (only occasionally stilted) prose, and her understated irony.

We can regard Mr Collins merely as a pompous man who has a very unromantic attitude to marriage, or we can see him as a satirical portrayal of the Church of England, an institution under the thumb of hereditary monarchs and landowners, making it morally compromised. His name, Collins, is that of one of the most widely-used peerages of the Georgian period, hinting that he is loyal to the establishment above all. Names are always significant in Jane Austen. Of course you can enjoy the book without realising any of that.

A tiny few enjoy Austen for her artful construction, the way she makes her stories argue a case, and reach an inevitable dénouement. It is Elinor Dashwood who marries romantically, for love, to a man who is at that point penniless, while it is Marianne who is persuaded to accept a sensible match, to a man whose devotion to her and comfortable inheritance make him eligible. And perhaps some enjoy Austen out of nostalgia for a society where marriage was still something that mattered.

Barchas refers to "working class" readers of Austen, but does she really think the match girls of London or the women who worked in cotton mills in Saltaire read Jane Austen in their (very limited) spare time? Did they while toiling long hours per day in wet streets or surrounded by a deafening clatter of machines, dream of marrying a Mr Darcy or Mr Knightley? Even if they did - and it is sad to imagine - they would have had no influence on canonical status. The academic canon was decided by the likes of F.R. Leavis sitting in his comfortable study in Selwyn College, Cambridge. (He condescended to include Austen in his list of worthy writers, then said nothing about her.)

There are plenty of silly books and articles about Jane Austen coming out all the time so why, you may ask, pick on this one? Because Barchas's book does not only insult Jane Austen - who will survive without difficulty. It also delivers a very nasty and pointless attack on an author with whom she is obviously unfamiliar, namely Lady Isabella St. John. Barchas does not like the fact that St. John wrote some mildly critical notes in a first edition of Mansfield Park. She regards this as presumptuous and retaliates by dredging up an unbelievably vitriolic review of one of St. John's own books, a review written in the 1830s, and telling us that it is "definitive". Of course it is no more definitive than the many insulting opinions people (such as Charlotte Brontë) have expressed about Austen's novels. Barchas knows next to nothing about St. John, but her derisive, secondhand comments have already been copied into that super-efficient apparatus for misinformation, Wikipedia.

So she has succeeded in prejudicing readers against an author who has done nothing to merit it, and who certainly deserves better. It is a great pity, and demonstrates how much harm is done by bad critics and the inward-looking academia industry. If academics exist for any purpose it should be to improve on the judgements of such opinionated, ignorant reviewers.

Is there any point in people like Professor Barchas purporting to "teach" Jane Austen? Is there any point at all in the academic circus? Teaching Austen at school level may be necessary because time passes and there are now many readers - the majority in fact - who need to have it explained to them that the place where N. takes M. for better or worse is a church and this is a wedding ceremony. They did not read it (as I did) as a child in the Anglican prayer book. They now need to be told that Lydia Bennet is likely to get pregnant if she elopes with Wickham, and that she cannot get the morning-after pill from the school nurse or nearest family planning clinic. They need to be told that Anne Elliot cannot simply go and train as a chartered accountant if she is dissatisfied with her life - nor as a nurse, doctor, teacher or mountaineering instructor. All this will surprise them.

But at university? That is where the pretentious twaddle takes over. There is an endless stream of academics busy trying to cram Austen into whatever trendy template comes along, arguing that her dislike of the Prince of Wales would have made her a Hillary Clinton supporter, or that Fanny Price's lack of athletic prowess makes her "disabled". They are worried that Jane Austen can be used as an icon of the so-called Alt-Right, who are far too "white, male and heterosexual". They think she needs to be de-stabilized with some verbose and opaque critical theory. They are embarrassed that she might be regarded as "cisheteropatriarchal" [sic]. A recent critic tries to argue that Austen's relationship with her sister is "erotic". All this is tiresome and absurd.

Jane Austen's values are not woke 21st century. Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion recommends Gowland's face cream to prevent aging, and the heroine, Anne, politely scorns the suggestion. Why? Because the product had long been advertised using a picture of the Duchess of Kingston, a celebrated beauty made notorious for her bigamy trial in the House of Lords. Her name had become a byword for an unchaste woman. Gowland is encoded with hidden implications of vanity, worldliness and licentiousness.

The "academics" who study Jane Austen simply copy errors from one book to another for decade after decade and call it scholarship. They cannot even record correctly the price that the publisher Richard Bentley paid for the copyright of Pride and Prejudice (surely one of the great bargains of publishing history). When I sent the correct figure to an "academic" journal, Notes and Queries, together with a photograph of the original document, the editor demanded that I rewrite the (very brief) text to say that a certain academic, their peer reviewer, who shall be nameless, had known this all the time but never bothered to print it.

Of course I didn't. I placed the information on the Academia.com website with the photograph, a form of evidence which Notes and Queries tells me it is unable to reproduce. Why - is it too white and cisheteropatriarchal?

The trouble is that far too many people write far too many books and articles about Jane Austen, and know far too little about the achievements of other writers. There is supposed to be something called Women's Studies, but you would never know it, from the attitude that people like Barchas take to any woman writer who is not in that safe, narrow, familiar list of "canonical authors". They heap contempt and hostility on what they simply don't know. What is needed is a fundamental change of attitude - an openness to widening the canon, an agreement that you don't judge what you haven't read, and a moratorium of at least five years, please, on extremely silly studies of those canonical authors.

======

Jane Austen's Lost Novel: Its Importance for Understanding the Development of Her Art. Edited with an Introduction and Notes by P.J. Allen. Troubador Publishing, 2021.

Comments

Post a Comment