There is a letter from "E. Craven" dated 21st April 1791 in the collection of the Wellcome Foundation in London. The library catalogue does not identify it as being from Elizabeth Craven, let alone cross-reference it. Nor does it connect it in any way with Dr. Edward Jenner, the celebrated physician. It is in the papers of the Reverend George Charles Jenner (1767-1846), who was in 1791 the vicar of Berkeley in Gloucestershire, a parish that included Craven's ancestral family home, Berkeley Castle.

The Berkeleys and Cravens had very close links with the Jenner family, who held this church living for many generations. The Earls of Berkeley were patrons of the parish and chose its incumbent. The Rev. George Jenner was the son of the Rev. Henry Jenner (1737-1798) previous vicar of Berkeley, who had succeeded his father the Rev. Stephen Jenner (1702-1754).

Dr Edward Jenner (1749-1823), the pioneer of vaccination, was another son of the Rev. Stephen Jenner and was thus the uncle of the Rev. George.

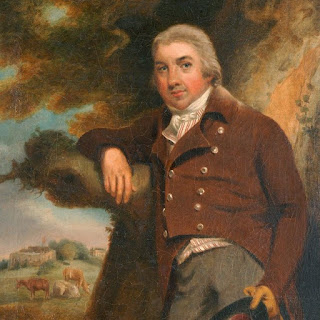

|

| Dr Edward Jenner, portrait by William Smith |

There are some mysteries about this letter. It is written on black-edged paper, indicating mourning, and it might be assumed to be written to the Rev. George Jenner because the outer sheet is addressed to "Mr G. Jenner, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England".

There is one inner sheet, with writing on both sides. The text is as follows:

"Dear Mr Jenner, I am coming to England, to show my adopted Brother England, and shall come to Bristol in the course of the Summer, when, if Lord Gruff is not in the castle, I shall see my dear Berkeley Castle, and show my Royal Brother my good friend Mr. Jenner. I have not time to say any more, only that I hope you are consulted about my Mother. I hear she is ill without knowing her Case. My Lord has had dreadfull epileptic attacks at Bath, out of which Dr Ash has/

dragged him.

So do not imagine this black border is for him, it is for the Margrave's wife, who died this winter. Don't take it into your head that my adopted Brother is a stiff German Prince - he talks English as well as I do, and is as gentle and English as possible. -- I have often told him you saved my life, for which he says he thinks himself much indebted to you.

Adieu, I remain, yours etc.

E Craven.

Pray answer this & direct it under cover to Henry Saville Starck Esq, Treasury Office, London. "

We know it is from Elizabeth Craven because of her allusions to "dear Berkeley Castle", where she spent much of her childhood, and to the German Margrave of Anspach, who would become her second husband though at this time she called him her adopted brother. His wife had just died at the beginning of 1791.

But to whom is she writing? Not, certainly, the Reverend George Jenner. Clearly, this letter is addressed to a doctor, not to a vicar. The references to consulting him about her mother's illness, the details about "my Lord" her husband's epileptic fits at Bath, and finally the mention of the person addressed having saved her life make it abundantly clear she is writing to a physician. Elizabeth Craven's mother, Lady Berkeley, died the following year, as did her husband, Lord Craven. And in her Memoirs, Elizabeth Craven remembers with gratitude the doctor who saved her life when she was a young woman - Dr. Edward Jenner. His treatment succeeded where that of all others had failed.

Is it possible that more than one member of the Jenner family had saved the life of Elizabeth Craven? Could a vicar perhaps have saved her from drowning in a particularly large font, or falling to her death from a bell-tower? When we look at the dates, this has to be ruled out. The Rev. George Jenner was born in 1767, so in 1783 when Elizabeth Craven left England to live on the Continent, he was aged only fifteen or sixteen. He was probably still at school. So the letter must be addressed to his uncle, the celebrated doctor whom she praises in her Memoirs.

It makes perfect sense that Craven wanted to introduce Dr. Jenner to the Margrave, who was interested in all scientific matters, particularly discoveries and improvements. By 1791 Dr. Jenner already had quite a reputation as a doctor with bold new ideas. He had been elected a member of the Royal Society in 1788. He did not carry out his first trial of vaccination until 1796, but he was very interested in all possible new advances, To meet the famous Dr. Jenner it would be worth travelling a long way.

Edward Jenner also lived in the village of Berkeley, close to his nephew, in a house that is now a Museum. He settled close to his roots, where he had grown up. So it seems that Elizabeth Craven wrote to him care of his nephew. Why did she not address the letter to Dr E. Jenner, Berkeley, Gloucestershire? It is odd, and hard to account for, but it must be so. Possibly she wrote to the young vicar too, enclosing her letter for his uncle in the same wrapper. The only other supposition would be that this letter was not originally sent in this wrapper. They could be mismatched. The outer sheet may belong to another letter.

|

Berkeley Church and churchyard where Dr Jenner is buried.

From a Victorian sketch. |

Who is the person referred to as Lord Gruff? It must be Craven's elder brother, Frederick, Earl of Berkeley, owner of the castle, with whom she had a touchy relationship. She was confident that if he was absent the servants at the castle would recognize her and allow her to show the Margrave around her ancestral home.

It is quite likely that Jenner visited Craven later when she moved back to England, and her younger brother Captain, later Admiral George Berkeley took a leading role in getting parliament to back Jenner's vaccination scheme financially. The Craven-Berkeley-Jenner links were crucial to his career.

The post-script added at the top of the first page is interesting too as it asks Dr. Jenner to reply care of Henry Saville Starck, Esq., at the Treasury Office, London. Starck was the husband of Craven's close friend, Anne-Marie Fauques de Vaucluse, the poet and novelist, so this indicates that the friends were still corresponding despite Craven's long absence on the Continent.

Hey Julia, I see the cover has a stamp that begins with 18, with a possible date of the 27th, and has something hand-written on it about August 26th, 1814, so I would venture to say the letter and the cover are mismatched. Interesting letter, though. I can't understand how she thought anyone would actually buy the "adopted brother" stuff. And I laughed when I read "Lord Gruff"!

ReplyDeleteThe explanation seems to be that this outer sheet belongs to another letter that is for some reason grouped with Craven's in the catalogue under MS 5288. It lists items 12-13 as a pair, Craven's being 12 while number 13 is a letter to Rev. George Craven from a Capt. E. Husson dated 21st August 1814. So the outer sheet belongs to the second letter, item 13, and has nothing to do with Craven's. The archive kindly sent me copies of the whole lot, but to lump it all together like this a bit misleading. Good work, Jill!

Delete