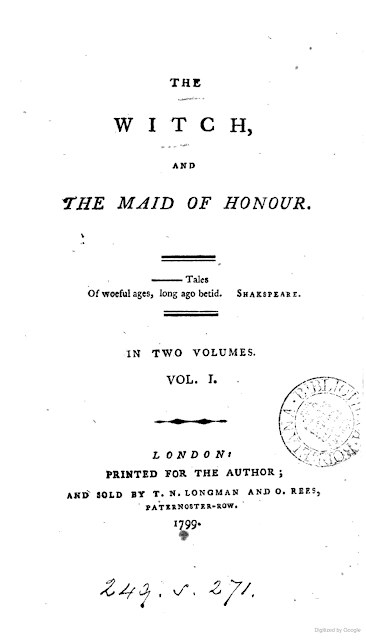

The Witch, and the Maid of Honour: A Lost Novel by Elizabeth Craven

The Witch and the Maid of Honour is a two-volume novel published privately and anonymously in London in 1799. It has a dedication to the Maids of Honour, signed "the Old Woman".

To THE MAIDS OF HONOUR.

LADIES,

The writer of the following trifle requests the honour of presenting to you the History of a Lady who formerly held the same exalted situation that you hold now. Permit Isabella Markham to solicit your patronage for the Author, who has the honour of being,

With great respect,

Your obedient humble Servant,

The OLD WOMAN.

Maj i, 1799.

So, unless there is some hidden jest, whoever wrote it is apparently a woman. The Dedication is followed by a mock preface that refers in a light-hearted way to John Locke's Essay Upon the Human Understanding. Then the novel begins.

The story is mainly set in or around Coombe Abbey, near Coventry in Warwickshire, a country house owned in 1799 by William, 7th Lord Craven, who was Elizabeth Craven's eldest son. He had inherited it from his father, the 6th Lord Craven, who inherited it from a long line of Cravens going back to the beginning of the 17th century. The house is built on the site of a twelfth-century Cistercian monastery, which at the Reformation was acquired by the Harrington family and converted into a fine, if gloomy, private mansion, set in a large estate with its own deer park.

This engraving, done in 1729, shows the house as it was then and as it still was when Elizabeth Craven, the writer, went there as the young wife of Lord Craven in the 1770s. The house is a Tudor Gothic building, occupying three sides of a courtyard that incorporates parts of the original mediaeval cloister. The pointed arches with their stone tracery are still there. The two wings are roughly symmetrical, and the design features gables, mullioned windows and tall chimneys, with a central cupola on the roof. Some ivy is growing up the lower sections of the walls. In fact it remained in much this state - apart from a neo-classical facade added on the other side of the building, not visible in this picture - until the alterations carried out in Victorian times, which did not improve the building and destroyed its symmetry.

Returning to the novel - the story concerns the Harrington family and the Princess Elizabeth, daughter of King James I, who lived at Coombe Abbey for some time in her girlhood in the guardianship of Lord Harrington. So this is a historical novel - perhaps the first in the English language, as it was published a year before Maria Edgeworth's Castle Rackrent, which is usually given that honour. I am in no haste to demote that excellent work for any reason, but I am just collating facts.

While The Witch and the Maid of Honour uses a historical setting, it takes many liberties with history and presents many events out of chronological order. The book is not divided into chapters, which is very unusual at this time. It is original, entertaining and hard to categorize. In various places, it makes use of free indirect speech, a technique whose invention is sometimes attributed to Jane Austen.[1]

The story is a curious one. Despite being set in and around this spooky abbey, the story is not really Gothic. As the book's Apology says, it does not contain ghosts or scary episodes. In fact, with its scepticism about witches, this is a rational Enlightenment tale. It includes various melodramatic incidents, such as attempted murders, and its complicated narrative structure, full of embedded narratives, is typical of that genre, but it is a very miscellaneous production and hard to classify, as it also contains bits of gentle comedy, mild satire, curious anecdotes, descriptions of rustic life and social criticism from a definitely feminist standpoint. It has much to say about the superstitious belief in witchcraft, which turns out to be nothing more than the persecution of harmless old women, particularly if they are poor. In the course of the book, after many ramifications, two such women are rescued from the menaces of a JP who is as ignorant and prejudiced as the local peasantry.

The book invents freely - for example, the real Lord Harrington did not marry a woman named Isabella Markham. Nor did Queen Elizabeth's favourite, the Earl of Essex, contract a secret marriage in his youth to a wife who died young. The execution of Essex, the Gunpowder Plot, and the death of Prince Henry are all mentioned but not necessarily in the right order. The battle of Zutphen here supposedly post-dates the Armada, and the Arbella Stuart rebellion happens after death of Queen Anne, wife of James I, but never mind [2].

Coombe Abbey from South 1810 Drawn by Davis engraved by Storer.

As soon as I came across this book, I had a strong suspicion that it was either by Elizabeth Craven or by one of her closest associates, because there is so much in it that is connected with her, characteristic of her, or points to her in some oblique way. The Dedication, the Preface and the Author's Apology, are all full of her typical whimsical, idiosyncratic manner. On the other hand, she is not known to have written full-length novels. All her known works of narrative fiction are relatively short.

We know that she read novels, including The Castle of Otranto, Gulliver's Travels, Vathek and Tristram Shandy (which she refers to in her Memoirs). A gossip column in the Rambler's Magazine reported at the time of her separation from her first husband, that she had got a settlement, enough to keep her in "rouge, culls [fools] and novels". [ 3] "Culls" also has connotations of prostitution because it is what prostitutes called their punters. So it is a very malicious comment. Any woman who read anything, even if it was Locke's Essay Upon the Human Understanding, was liable to be reported somewhat scathingly as merely reading novels, by implication silly and worthless things. Did Elizabeth Craven publish any other works without her name on the title page? Yes, in fact she did. Her story Modern Anecdote of the Ancient Family of the Kinkvervankotsdarsprakengotchderns: A Tale for Christmas 1779, had no author's name anywhere, only a preface to Horace Walpole that provided many clues. The same is true of Letters to Her Son, published in 1784 anonymously, whith a preface that provides plenty of broad hints to help the reader to identify her.[4]

Rather than jumping to any conclusions, I have considered various possibilities for attribution, and looked at some of the writers in Elizabeth Craven's close circle as hypothetical authors. Her friend Mrs Anne Damer is one possible candidate I have mulled over. She wrote the novel Belmour (a tribute to Craven herself, published in 1801) so we know she could write fiction of this length and complexity. Another candidate is Anne-Marie de Vaucluse, a.k.a Mme Starck, the governess of Elizabeth Craven's children, who became her firm friend and correspondent for many years. Vaucluse was a novelist and for some time reliant on her income from novel-writing to live. She favoured exotic oriental subjects for which there was a ready market. Both she and Damer were a little older than Elizabeth Craven, and so might have jestingly signed themselves "The Old Woman".

Clearly the author was a person who was familiar with Coombe Abbey and its history, a history bound up closely with that of the Craven family. In the story, Princess Elizabeth arrives at Coombe Abbey to be placed in the care of Lord Harrington. It is true that King James I's daughter, Elizabeth Stuart, passed her childhood at Coombe Abbey under Lord Harrington's guardianship. She was somewhat younger than the princess in the novel but there is a basis of truth in the story. This Princess was the future Queen of Bohemia, ancestress of the House of Hanover and a great-great-great aunt of Elizabeth Craven, through her father's family, the Berkeleys. And this Stuart Princess was also closely linked to the Cravens. In c.1620, the first Lord Craven bought Coombe Abbey from the Harrington family. Later the same Lord Craven built Ashdown Park in Berkshire for Princess Elizabeth when she returned to England in exile in the 1650s. Both Ashdown Park and Coombe Abbey were inherited by his descendant, William Craven, and so Elizabeth Craven, the writer, had many reasons to take a close interest in the Winter Queen. She was descended from her, and soon after her marriage found herself living in two houses which had once been home to Elizabeth Stuart. Coombe Abbey was full of paintings of the Stuarts, and so was Ashdown House. In her Memoirs, Elizabeth Craven writes about how interested she was in the history of Coombe Abbey, and how the steward, touched by her curiosity, showed her old documents one of which concerned a loan given to the Queen of Bohemia by the first Lord Craven. [5]

A photograph of Coombe Abbey taken around 1860, showing how the Tudor building remained largely intact until the late Victorian era. Only a section on the western side has been altered.

What else can we discover about the author from the book? She - assuming she is a woman - is very fond of quoting Shakespeare, but there is nothing unusual about that. She is very interested in gardens, and in garden design. Lady Harrington displays a great interest in horticulture and has a dialogue with a gardener. There are many details of the garden at Coombe Abbey, and even of the vicarage garden. [6] In volume 2 this interest is displayed again when Lady Matilda lodges with the Greens and creates a garden. She starts from scratch - design, layout, planting, and goes on to get permission to build a grotto. Gardening and garden design was a lifelong passion of Elizabeth Craven. She had a grotto in her English garden at Ansbach, and another smaller one in her last garden, at her villa in Naples. She may have been inspired by Pope's Grotto at Twickenham, near Strawberry Hill, a place she visited often in the 1770s. Anne Damer too must have been familiar with this celebrated example. The author's taste in gardens is altogether very English and Romantic, and her description of the countryside make it clear that she strongly approves of unpruned trees, left to flourish in their natural shapes, rather than formal topiary.

It was one of those fine evenings just between summer and autumn; the air was extremely warm; not a breath of wind stirring, and the grass-fields had recovered their verdure since the hay had been carried off; the corn fields were in full ear, and the grain in the milk, as the farmers express it. The sun was almost setting, the full-orbed moon rising, and the different lights so beautifully disposed, that to a painter's eye, it was one of the finest scenes in nature. The hill was partially covered with forest trees of a very old growth - oak, ash, beech, and sycamore; no injurious axe had ever cropped their flowing honours, but they were spread in full beauty as nature directed. —Tufts of broom grew in patches upon the top and fides of the hill ; and at the bottom, next the road, was a low quickset hedge, and a little stream of water. On the other side of the road was the White Cottage. There was also a very large ash, which had many years lost its head by some tremendous storm, on which account the branches had spread much wider from the lower part of the tree - its roots came out of the earth in many a fantastic winding upon the sides of the hill, and mouse-ears, hare-bells, and other wild flowers, grew profusely upon, the slope.[7]

All of that corresponds to Elizabeth Craven's known tastes and opinions, as she expresses them in her letters and elsewhere.

The story features a lot of clever women, who are not afraid to express their opinions in a very forthright way. Lady Harrington is one of them. Her husband remarks that she knows more about politics than he does. When the subject of witches arises, he is at first inclined to believe in them, but she stoutly refuses and argues with perfect logic, that if an old woman really had the power people imagine, to cast spells or cure diseases, she would surely not be living in poverty and hardship: she would use her powers to improve her own lot [8]. Her mother, Lady Markham, is another shrewd woman who outwits the old Earl of Essex. Lady Harrington's daughter Matilda is also rather fond of expressing herself in strong terms. When she takes a dislike to the witch-hunting JP, she calls him a "reptile ". [9] Most Georgian heroines don't call people reptiles.

The author is someone with a knowledge of English music, for she throws in a tribute to "Mr Lawes" a composer of “wild genius”. [10] William Lawes was a musician who died in the English Civil War, and Milton wrote a sonnet to him. We know that Elizabeth Craven had a great enthusiasm for music and played the piano and the harp.

The story features a tournament at the court of King James I, given to celebrate the betrothal of the Princess to the Elector of Palatine. It is a fine chivalric ritual, narrated by somebody with a taste for spectacle and theatricality. Without any doubt, Craven possessed that. She wrote and produced many plays, ballets and masques, that were performed on the private or public stage.

The author appears to be someone with little faith in conventional doctors, and a preference for herbal folk remedies. She also has a liking for vernacular language, and for reproducing the speech of servants or country people, with comic effect, for instance including malapropisms. Both of these things are definitely true of Elizabeth Craven, as many of her poems and plays attest. [11]

At the end of the book there is an Author's Apology written in an ironic, bantering style that is highly typical of Elizabeth Craven. Here, as in the Dedication, I have a strong feeling that I can hear her personal voice. She pronounces that the book has many weaknesses. “First, it contains too many serious commonplace reflections.” That is being rather severe on herself. Then she apologizes for it not being in the fashionable “horrid” manner “The horribly grand is not sufficiently worked up to make your hair stand on end, your flesh creep upon your bones or your eyeballs start from their sockets.” [12] While the first volume does achieve a dark and grim atmosphere at times, the second volume does not maintain it throughout, and often reveals that the author’s principal impulse as a writer is towards comedy.

She explains that there is not much romance or sentimentality in the novel as she wears spectacles now to read or write, and would not want to be continually mopping teardrops off them. We know that Elizabeth Craven wore spectacles for reading in later life.[13]

Assuming that the dedication is addressed to the royal Maids of Honour, we know that Craven was acquainted with at least one of them, Miss Caroline Vernon, whose brother Henry was rather well known to her too. She might fit the bill, as she never married. There was also Elizabeth Craven's niece, Lady Elizabeth Forbes, who was a lady in waiting to the Princess of Wales, wife of the future George IV. We know that Lady Elizabeth Forbes was a visitor at Benham a few years after this, as she is featured in a drawing by John Nixon done in 1805.[14] However, we should beware of taking the Dedication too literally. I wonder if it may refer to somebody who perhaps acted the roles of maids of honour in one of Craven's frequent theatrical ventures. There were two girls called the Miss Berkeleys whom she fostered and referred to as her nieces or cousins, who did act in her productions regularly, and might have enjoyed reading a novel of this kind. They might have acted her maids of honour when she acted such a rôle as Margaret of Anjou.[15]

Altogether, this appears to me to be enough evidence to justify a hypothesis that Craven is the author of The Witch and the Maid of Honour, and unless somebody in the the academic community comes up with some definite proof that she could not have written it, or that it was written by another author, I am going to classify it tentatively as being Craven's work.

As the Apology says, the book is not a love story. That is indeed what is so curious about it. There is no Valancourt, no Lord Orville and no Mr Darcy. There are some romances in the sub-plots. but it is essentially a story about two women friends who are brought up together, as sisters, lose touch for many years, and are finally re-united, to the great delight of both. One of them, Isabella Markham, becomes a maid of honour to Queen Elizabeth, then marries Lord Harrington and becomes mother of a numerous family. They live at Coombe Abbey and are entrusted with the guardianship of the princess. The other, Matilda Devereux, leads a very different life, in obscurity and much of the time in hiding as a fugitive. After many vicissitudes, she disguises her face to appear disfigured, and becomes a veritable recluse, living in a small isolated cottage on the outskirts of a village whose inhabitants decide she is so odd, she must be a witch. The village is very close to Coombe Abbey, where unknown to her, her childhood friend is living. She does not know that "Lady Harrington" is the married name of Isabella Markham - a typical problem of female invisibility. Lady Harrington is determined to rescue all witches and so eventually the identity of the mysterious Old Woman is revealed.The eventual re-union of these two women brings about the resolution of the story. Matilda Devereux refuses to marry, and while there are a handful of marriages at the end of the narrative, they are narrated in a light hearted and cursory way as if they are more of a convention than the climax of the book. The real story is concluded when the two friends who have been estranged are re-united. A novel about friendship between two women is both unusual and rather welcome.

Elizabeth Craven did without doubt have friends she knew in her youth and was parted from for many years, including the Vernon sisters and Anne Damer both of whom she knew in her teens and her twenties, and then met again when she returned to England in the 1790s after many travels. Anne was a sculptor and writer who lived an unconventional life, finding independence in widowhood. She was not too prim or proper to visit Elizabeth Craven at Hammersmith when the starchier members of society stayed away. And there were plenty of other friends too, but I am not sure that this novel is just about two friends who are re-united. That is too straightforward. I suspect that there is more to it than that.

One clue is in the Preface, which tells us that Locke's Essay upon the Human Understanding is "a history book, ... of what passes in a man's own mind". And it is possible that in some ways The Witch and the Maid of Honour is a history book of what passes in a woman's own mind.

Lady Harrington has certain things in common with Elizabeth Craven, as she is the wife of the nobleman who owns Coombe Abbey and the mother of a family of two sons and two daughters - not quite as large as Elizabeth Craven's, but a numerous brood. She might well be envied for such a social position. She is intelligent, forthright, opinionated and very fond of reading and gardening. She definitely does not believe in witches and when her opinions clash with those of her husband and the local JP she is resolved to prove them wrong and herself right. However, the author does not sign herself "Lady Harrington". She signs herself "The Old Woman".

It is possible to find certain less obvious things that the "Old Woman" alias Lady Matilda Devereux, also has in common with Elizabeth Craven. Lady Matilda is almost an orphan as her mother dies at her birth, and her father does not want to acknowledge her. There is a shadow over her, and many people believe she is illegitimate, which would of course be a disgrace. Moreover, because of the circumstances of her birth - which are pretty melodramatic and Gothic - her family on both sides want to kill her. She cannot appear at court and or in public at all. She has to conceal her whereabouts, change her name and move from place to place, living in hiding. At one point, she actually shelters in a convent, for in this rather vague impression of Tudor England, there are some left which seem to have avoided Dissolution.

While Elizabeth Craven was not literally a fugitive in fear of her life, she was pilloried, ostracized and disgraced in a very painful way. The gossip could be cruel. So could snubs and exclusion. She once got a letter from her own daughters saying they could not receive her. All of them were reconciled with her later, but the wound was a hurtful one. And this does not just have to be about the fall-out from her marital break-up. The sense of being a person with much to conceal, living in secret, could go much deeper than that. I wonder if Matilda Devereux represents the hidden side of her, the secret and vulnerable self always in hiding, because she was too passionate, too emotional, too sexual, too assertive and rebellious. Married very young, under parental pressure, she knew what it was to have to hide her feelings, conceal her true impulses and desires, and suffer social hostility and disapproval. Women who broke the rules faced harsh blame and ruin. Coombe Abbey meant something very personal and special to Elizabeth Craven, as it was there that she first fell in love, a secret she could express only in poetry. In the course of her life she had many passionate, clandestine love affairs. Somebody who knew her and Lord Craven in early years of their marriage recorded that she had been, even at that time, profoundly unhappy. [17] She was in a social position that made her widely envied, and she was often described as being lively and vivacious, but part of herself had always been in hiding.

When Matilda Devereux has no friends or family to shelter her, she is left in the care of Lady Coniers, whose son William proposes to her. She turns him down, because although he is the heir to a large fortune and several estates, he is dull and poorly educated. She goes on turning him down until after some years he eventually marries somebody else.[18]. I cannot help noticing that his initials are the same as those of William Craven, the husband Elizabeth undoubtedly regretted marrying.

Among the adventures Lady Matilda relates in volume 2, she recalls how she found a friend in a cheerful Mr Green, a country squire who enjoys hunting, shooting and fishing. He welcomed visitors because, as he complains, his ancestor built him an enormous house which is now far too large for him, and which he cannot even afford to keep up. She moves into this mansion as a lodger and becomes virtually a member of the family. I wonder if there is a private joke here. Mr Green's predicament is in a way rather like that of the Margrave of Anspach, whose father and grandfather had built extravagant palaces and left him and his little principality crippled by debt. He rarely occupied the grand palaces at Anspach or Bayreuth, preferring to live in a hunting lodge at Triesdorf.

The heraldic shield of Ansbach, was green - a green shield with three fish on it - so the name Mr Green could be thought to fit him nicely.

What makes this novel a feminist book is the way it highlights the superstitious belief in witches, a belief that amounted to the persecution of harmless women who might be thought to be odd, non-conformist or peculiar. There is great compassion for those who are truly poor and living in hovels, such as old Mrs Gaps. Lady Harrington has a strong sense of responsibility that something should be done to help them. If the author identifies with the Old Woman, that is to say with Matilda Devereux, then she is identifying with the witches who were hunted, demonized and burnt. She is comparing the treatment of divorced or separated women such as herself to a witch-hunt, and sees both as part of the general oppression of her sex, which has gone on for centuries. Even though one or two women become queens, they are anomalies and the vast majority are in a situation that is powerless and vulnerable, subjected to lingering prejudice and superstition.

If Elizabeth Craven was the author of The Witch and the Maid of Honour then it is understandable that her friend Anne Damer, who had not previously written anything, should soon after this date, write her only novel, Belmour, in which Coombe Abbey also figures largely. Reading The Witch and the Maid of Honour may have spurred her to attempt a novel herself. I wonder if she, Craven and some of their friends visited Coombe Abbey, perhaps for Christmas in 1798.

With the exception of such notice by Craven's own friends, The Witch and the Maid of Honour has been totally neglected from the time of publication up until the present day. It got one perfunctory review, and has been listed in bibliographical works. It has never been re-printed and I cannot find any critical appreciations of it. This novel certainly deserves more attention, if only for possibly being the first historical novel written in the English language. A good modern edition of it is amply justified for study purposes. It is an accomplished work in many respects and ought to be part of the canon of English literature. Establishing its attribution to Elizabeth Craven raises her stature as a writer and strengthens her claim to be considered one of the most significant literary figures of her time.

The book Elizabeth Craven: Writer, Feminist and European, is now available in paperback: https://vernonpress.com/book/394

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/Elizabeth-Craven-Writer-Feminist-and-European-hardback-NEW-Vernon-Press-2017/202540437722?hash=item2f2859d0da:g:bccAAOSw8OFcF3-k:rk:1:pf:0[1] The Witch and the Maid of Honour,1:26.

[2] The Witch and the Maid of Honour,1:101 and 141.

[3]

Rambler’s Magazine July 1784, p.159.

[4] Elizabeth Craven, The Modern Philosopher, Letters

to Her Son and Verses on the Siege of Gibraltar, by Elizabeth Craven.

Translated and edited by Julia Gasper, Cambridge Scholars Press, 2017.[5] Elizabeth Craven, Memoirs of the Margravine of Anspach (1826), 2:93.

[6] The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 1:192-3 and 1.211.

[7] The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 2:19.

[8] The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 2:3.

[9] The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 2:54.

[10] Lawes The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 2:194.

[11] The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 1:245 and 1:222.]

[12]

The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 2:215.

[13]

Julia Gasper, Elizabeth

Craven, Writer, Feminist and European, Vernon Press 2017, chap 6.

[14]

See earlier blogpost, “A Production of The Beggars' Opera at Benham in 1805”.

[15] Julia Gasper, Elizabeth Craven, Writer, Feminist and European,

Vernon Press 2017, chapters 5 & 6.

[16]

Craven, Memoirs (1826), 1:94.

[17]

Olivia Wilmot Serres, The Life of the Author of the Letters of Junius: The

Rev. James Wilmot, D.D., Late Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford, Rector of

Barton-on-the-Heath, and Aulcester, Warwickshire, and One of His Majesty's

Justices of the Peace for that Country: with Portrait, Fac Similes, &c, (London:

Williams,Walker and Hatchard, 1813), 75.

[18] The Witch and the Maid of Honour, 2:170.

Comments

Post a Comment