Elizabeth Craven: Myths and Fallacies

We've all come across articles we disagree with from time to time but some are just so inaccurate that the unwary public needs to be warned against them.

Elisabetta Marino's article "Constructing the Other: Reconstructing Herself" - A Journey Through the Crimea to Constantinople by Lady Elizabeth Craven" in the book The West in Asia and Asia in the West: Essays on Transnational Interactions, edited by herself and Tanfer Emin Tunc (1) is one of these.

The blurb claims, "This collection of new essays examines the “transnational turn” in cultural studies between Asia and the West. Drawing on literature, history, culture, film and media studies, scholars from a range of disciplines explore the constructs of “Asia” and “the West” and their cultural collision." Hmmm. Well, most of the collision I can find is with the facts.

I will not carp too much about the assumption that Turkey is part of Asia - although according to 18th century ideas, Turkey was in Europe and Turkish events were reported in periodicals such as the Mercure de Hollande under that heading. That doesn't matter hugely, but the glaring misrepresentation of Craven herself has to be corrected.

It seems to me that Ms Marino, who appears to work at the University of Rome (10), has not read Craven's travelogue with close attention, and she has relied rather a lot on quotations and opinions found in the books and articles she lists in her bibliography. (11) Her article is a very hostile one, and her hostility is not supported with good arguments. In fact, the entire essay is unreliable and liable to mislead students rather than instructing them. Since Marino is one of the editors of this book, that is a very bad indicator and I suggest readers give it a miss, and libraries do not bother to buy it.

Most of the recently-published essays on Elizabeth Craven by so-called academics are negative and dismissive. A case in point is "Strolling Roxanas", by the Australian Katrina O'Loughlin, in the mainly-Australian collection Spaces for Feeling: Emotions and Sociabilities in Britain, 1650-1850 edited by Susan Broomhall. O'Loughlin writes repeatedly of Craven's "foolishness" and dreadful wickedness and never at any point shows any knowledge of her works, or indeed the slightest interest in it. She is very interested in what other people at the time said about Elizabeth Craven, and not at all interested in what Craven herself wrote or did. However the only substantial factual inaccuracy is the statement that the Margrave of Anspach was thirty years older than Elizabeth Craven. He wasn't. (12)

For a more accurate and reliable account of who Elizabeth Craven was, what she did and what she wrote, see Elizabeth Craven: Writer, Feminist and European (Vernon Press, 2017).

Elisabetta Marino's article "Constructing the Other: Reconstructing Herself" - A Journey Through the Crimea to Constantinople by Lady Elizabeth Craven" in the book The West in Asia and Asia in the West: Essays on Transnational Interactions, edited by herself and Tanfer Emin Tunc (1) is one of these.

The blurb claims, "This collection of new essays examines the “transnational turn” in cultural studies between Asia and the West. Drawing on literature, history, culture, film and media studies, scholars from a range of disciplines explore the constructs of “Asia” and “the West” and their cultural collision." Hmmm. Well, most of the collision I can find is with the facts.

I will not carp too much about the assumption that Turkey is part of Asia - although according to 18th century ideas, Turkey was in Europe and Turkish events were reported in periodicals such as the Mercure de Hollande under that heading. That doesn't matter hugely, but the glaring misrepresentation of Craven herself has to be corrected.

Near the beginning, Marino claims that on separation from her first husband (in 1783) Craven got no financial settlement and had to live on charity from her friends such as Walpole, Sir Joshua Reynolds, William Beckford, Samuel Johnson and David Garrick. (2) This is simply not true. Where did she get that idea from? In fact when Craven parted from her first husband (in 1783) she got a settlement sufficient for her to live in a rented house in France with her son Keppel and go into Parisian society, where she mixed with some of the best. None of the people listed by Marino ever gave her any money at all and she never asked anybody for charity. She always had servants, a carriage, a piano, her harp, books and enough money to buy clothes, judging from Jeremy Bentham's description of her in Paris as a "woman of fashion". She was no longer rich, but she was very well off compared to most people.

Next, Marino complains that Craven had a dairy farm built wherever she lived so she could play the role of "model housewife and domestic goddess". (3) Craven did have a small dairy in France - not a dairy farm, but a dairy, as many country dwellers did. It never occurs to Marino that Craven might have wanted a cow or two in order to get the milk for herself and her young son, who was then aged four. In 1783, you couldn't just stroll into a supermarket and buy pasteurized milk in sterilized containers, secure in the knowledge that all farms were inspected and kept up to legal standards of hygiene and animal health. Craven was very interested in the quality of food and would not have wished to touch the sort of milk that was usually sold in cities at this date. While such things as TB and brucellosis were not yet understood scientifically, wise people were aware that the only real guarantee of safe milk was to get it from cows you knew, and whose health you could check on regularly. Craven was used to having her own dairy at Benham. She always insisted on fresh milk for her family and she herself would when ill revert to living on milk, which was a very unusual regime - but then Craven was always a bit of a health-food crank. That may be why she brought up seven very healthy children, and lived to an advanced old age.

Marino then complains that in Craven's travelogue A Journey Through the Crimea to Constantinople there is a "Fictitious male friend she had originally intended to write her letters to". (4). This is curious, I cannot find any trace of him. I have read both editions of Craven's travel letters now, rather carefully, and he does not seem to be there. From first to last the letters are addressed to the Margrave of Ansbach, with whom she had started a friendly relationship in Paris and who eventually became, in 1791, Craven's second husband. Marino claims that this fictitious friend is "replaced by the Margrave of Ansbach with whom she pretended to have a chaste and innocent relationship". But what evidence can she find that their relationship at this date was anything apart from chaste and innocent? When I was researching my book, I came to the conclusion that Craven, who had never yet visited Ansbach at this point in her life, was not in fact the Margrave's mistress until some time later - and she could hardly have been his mistress while making the Journey as they were several hundred, sometimes thousands of miles apart. Marino is in such a hurry to castigate Craven and denounce her for transgressing the rules of sexual behaviour as they existed in 1785, that she never checks her dates, facts or primary sources.

Next, Marino complains that Craven had a dairy farm built wherever she lived so she could play the role of "model housewife and domestic goddess". (3) Craven did have a small dairy in France - not a dairy farm, but a dairy, as many country dwellers did. It never occurs to Marino that Craven might have wanted a cow or two in order to get the milk for herself and her young son, who was then aged four. In 1783, you couldn't just stroll into a supermarket and buy pasteurized milk in sterilized containers, secure in the knowledge that all farms were inspected and kept up to legal standards of hygiene and animal health. Craven was very interested in the quality of food and would not have wished to touch the sort of milk that was usually sold in cities at this date. While such things as TB and brucellosis were not yet understood scientifically, wise people were aware that the only real guarantee of safe milk was to get it from cows you knew, and whose health you could check on regularly. Craven was used to having her own dairy at Benham. She always insisted on fresh milk for her family and she herself would when ill revert to living on milk, which was a very unusual regime - but then Craven was always a bit of a health-food crank. That may be why she brought up seven very healthy children, and lived to an advanced old age.

Marino then complains that in Craven's travelogue A Journey Through the Crimea to Constantinople there is a "Fictitious male friend she had originally intended to write her letters to". (4). This is curious, I cannot find any trace of him. I have read both editions of Craven's travel letters now, rather carefully, and he does not seem to be there. From first to last the letters are addressed to the Margrave of Ansbach, with whom she had started a friendly relationship in Paris and who eventually became, in 1791, Craven's second husband. Marino claims that this fictitious friend is "replaced by the Margrave of Ansbach with whom she pretended to have a chaste and innocent relationship". But what evidence can she find that their relationship at this date was anything apart from chaste and innocent? When I was researching my book, I came to the conclusion that Craven, who had never yet visited Ansbach at this point in her life, was not in fact the Margrave's mistress until some time later - and she could hardly have been his mistress while making the Journey as they were several hundred, sometimes thousands of miles apart. Marino is in such a hurry to castigate Craven and denounce her for transgressing the rules of sexual behaviour as they existed in 1785, that she never checks her dates, facts or primary sources.

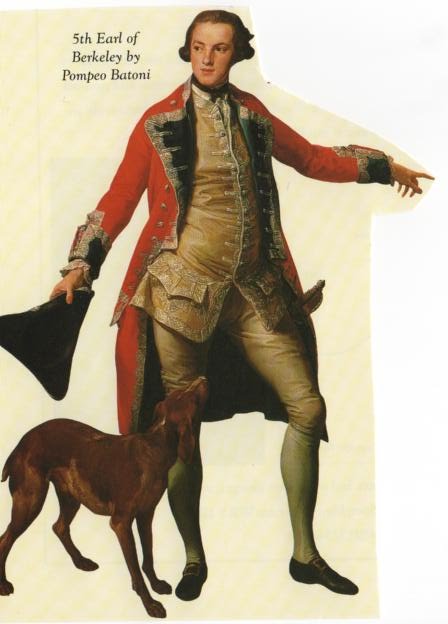

Marino complains that Craven "claims to travel alone" and was "quite inconveniently accompanied by a gentleman" - but where does she claim to travel alone? Where in the text can Marino find any such statement? In the texts I have read - and I have read both editions - Craven is just discreet and enigmatic about it. She is writing a travelogue, not an intimate sex diary. And while it is true that somebody did accompany her, what was inconvenient about it? As a matter of fact Henry Vernon, her companion, happened to be a war-hero and an outstanding equestrian sportsman, so as a companion on a long journey he had distinct advantages. Marino quotes Horace Walpole's comment that the companion was Elizabeth's "cousin Vernon", and if we look into the facts he was a distant cousin of the Berkeleys, but so what? (5)

Further down, Marino claims that when Craven reached the Turkish capital she "remained aloof and isolated and did not go out to see the sights of Constantinople". (6) That is far from the truth. In the book, Craven describes how, while staying in the Pera district, she would cross the river in a boat and then take a sedan chair to see all the great sights of the ancient Byzantine city. She started with Santa Sophia and the huge market nearby. In fact the French ambassador obtained a special pass entitling her to see inside all the major sights, including mosques, palaces, and all the different quarters of the city. She spent many weeks exploring them, and did her own sketches of some of the sights - which are included in the book, as anyone can see without even taking the trouble to read the text. She walked six miles to Beykos to see a famous palace there, and also took a boat trip to Tophana. She even took the trouble, which was considerable, to get introduced to some Turkish women, in the household of a Pasha, whose home and costume she describes in great detail.

Further down, Marino claims that when Craven reached the Turkish capital she "remained aloof and isolated and did not go out to see the sights of Constantinople". (6) That is far from the truth. In the book, Craven describes how, while staying in the Pera district, she would cross the river in a boat and then take a sedan chair to see all the great sights of the ancient Byzantine city. She started with Santa Sophia and the huge market nearby. In fact the French ambassador obtained a special pass entitling her to see inside all the major sights, including mosques, palaces, and all the different quarters of the city. She spent many weeks exploring them, and did her own sketches of some of the sights - which are included in the book, as anyone can see without even taking the trouble to read the text. She walked six miles to Beykos to see a famous palace there, and also took a boat trip to Tophana. She even took the trouble, which was considerable, to get introduced to some Turkish women, in the household of a Pasha, whose home and costume she describes in great detail.

Having overlooked all of this, Marino writes angrily about Craven's "unconcealed and deep contempt towards the Turks".(7) If I were marking her English for GCSE purposes I would knock off a mark here for the use of the wrong preposition. It ought to be "contempt for" - please see a learner's dictionary, Miss Marino! Then, why are there no quotations to back up the indictment? Craven mixes praise and criticism freely and rather famously wrote "The Turks in their conduct towards our sex are an example to all other nations."

It is of course true that Craven reveals a deep sympathy for the Greek Orthodox Christians who still made up about half the population of Istanbul at this period. The number was declining for many reasons, but the Christians were still very much there, and were very much the underdog, and Craven quite rightly visited them and includes many very minute and fascinating descriptions of their costume and habits. She sympathized with their predicament under oppressive laws. Marino accuses Craven of having "imperialistic" tendencies but funnily enough seems to have no objection to the imperialist subjugation of Greece and the Balkans by Turkish rulers.

It is of course true that Craven reveals a deep sympathy for the Greek Orthodox Christians who still made up about half the population of Istanbul at this period. The number was declining for many reasons, but the Christians were still very much there, and were very much the underdog, and Craven quite rightly visited them and includes many very minute and fascinating descriptions of their costume and habits. She sympathized with their predicament under oppressive laws. Marino accuses Craven of having "imperialistic" tendencies but funnily enough seems to have no objection to the imperialist subjugation of Greece and the Balkans by Turkish rulers.

Marino tells us that when Craven returned to live in England in the 1790s, no ladies of fashion visited her. Well, just a few - the Duchess of York, the Duchess of Gordon, the Countesses of Jersey, Corke and Buckinghamshire - did manage to elbow their way in through a host of fascinating people from the arts - musicians, actors, painters and poets - who crowded to her house. Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, the painter, Madame Grassini, the opera-singer, and Anne Damer, the sculptor and novelist, were among Elizabeth Craven's friends and might have consoled her for the absence of some dull "ladies of fashion". (8)

For good measure, Marino throws in at the end a tale of how Craven in her old age in Naples entertained the possibility of marrying King Ferdinand That old piece of gossip simply never had any basis at all. Why revive it now? (9)

For good measure, Marino throws in at the end a tale of how Craven in her old age in Naples entertained the possibility of marrying King Ferdinand That old piece of gossip simply never had any basis at all. Why revive it now? (9)

It seems to me that Ms Marino, who appears to work at the University of Rome (10), has not read Craven's travelogue with close attention, and she has relied rather a lot on quotations and opinions found in the books and articles she lists in her bibliography. (11) Her article is a very hostile one, and her hostility is not supported with good arguments. In fact, the entire essay is unreliable and liable to mislead students rather than instructing them. Since Marino is one of the editors of this book, that is a very bad indicator and I suggest readers give it a miss, and libraries do not bother to buy it.

Most of the recently-published essays on Elizabeth Craven by so-called academics are negative and dismissive. A case in point is "Strolling Roxanas", by the Australian Katrina O'Loughlin, in the mainly-Australian collection Spaces for Feeling: Emotions and Sociabilities in Britain, 1650-1850 edited by Susan Broomhall. O'Loughlin writes repeatedly of Craven's "foolishness" and dreadful wickedness and never at any point shows any knowledge of her works, or indeed the slightest interest in it. She is very interested in what other people at the time said about Elizabeth Craven, and not at all interested in what Craven herself wrote or did. However the only substantial factual inaccuracy is the statement that the Margrave of Anspach was thirty years older than Elizabeth Craven. He wasn't. (12)

For a more accurate and reliable account of who Elizabeth Craven was, what she did and what she wrote, see Elizabeth Craven: Writer, Feminist and European (Vernon Press, 2017).

(1) The West in Asia and Asia in the West: Essays on Transnational Interactions, Jefferson N.C, McFarland, 12 Jan 2015, pp. 34- 45.

(2) Ibid p. 36.

(3) Ibid p.37.

(4) Ibid p.38.

(5) Ibid p.39.

(6) Ibid p.40

(7) Ibid p.42

(8) Elizabeth Craven: Writer, Feminist and European, Vernon Press 2017.

(9) The West in Asia p.44.

(10) https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Elisabetta_Marino2

(11) Marino says that she has consulted Kostova Ludmilla, "Constructing Oriental Interiors:Two Eighteenth-Century Women Travellers and Their East.” Eds. Vita Fortunati, Rita Monticelli, and Maurizio Ascari. Travel Writing and the Female Imaginary. (Bologna: Pàtron, 2001) 17–33 and Katherine Turner, 'From Classical to Imperial: Changing Visions of Turkey in the Eighteenth Century', in Steve Turner ed., Travel Writing and Empire: Postcolonial Theory in Transit (London: Zed Books, 1999). Both seem to have left their mark.

(12) Oxford and NY, Routledge, 2015.

(2) Ibid p. 36.

(3) Ibid p.37.

(4) Ibid p.38.

(5) Ibid p.39.

(6) Ibid p.40

(7) Ibid p.42

(8) Elizabeth Craven: Writer, Feminist and European, Vernon Press 2017.

(9) The West in Asia p.44.

(10) https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Elisabetta_Marino2

(11) Marino says that she has consulted Kostova Ludmilla, "Constructing Oriental Interiors:Two Eighteenth-Century Women Travellers and Their East.” Eds. Vita Fortunati, Rita Monticelli, and Maurizio Ascari. Travel Writing and the Female Imaginary. (Bologna: Pàtron, 2001) 17–33 and Katherine Turner, 'From Classical to Imperial: Changing Visions of Turkey in the Eighteenth Century', in Steve Turner ed., Travel Writing and Empire: Postcolonial Theory in Transit (London: Zed Books, 1999). Both seem to have left their mark.

(12) Oxford and NY, Routledge, 2015.

Comments

Post a Comment